Introduction

The enmity between developers and DBAs is both legendary and persistent. Developers get frustrated when DBAs take so long to do the simplest of tasks, and DBAs are disparaging of developers who want the database to do nothing more than be persistence for their app.

We often make fun of this tension between the camps, but it is actually indicative of a much deeper challenge that comes from two fundamentally different viewpoints of data structures. Both viewpoints are equally valid although they result in data being held in entirely different ways, and converting from one to the other is problematic. This has been described as object relational impedance between java objects and a relational database, and whilst this is one incarnation of the contradictory viewpoints, it is not the only one – the challenge lies in the fundamental data structures themselves, not in the physical storage model per se.

So, let’s look at the two viewpoints. If you know all this already feel free to skip this next section.

Entity-Object Structure

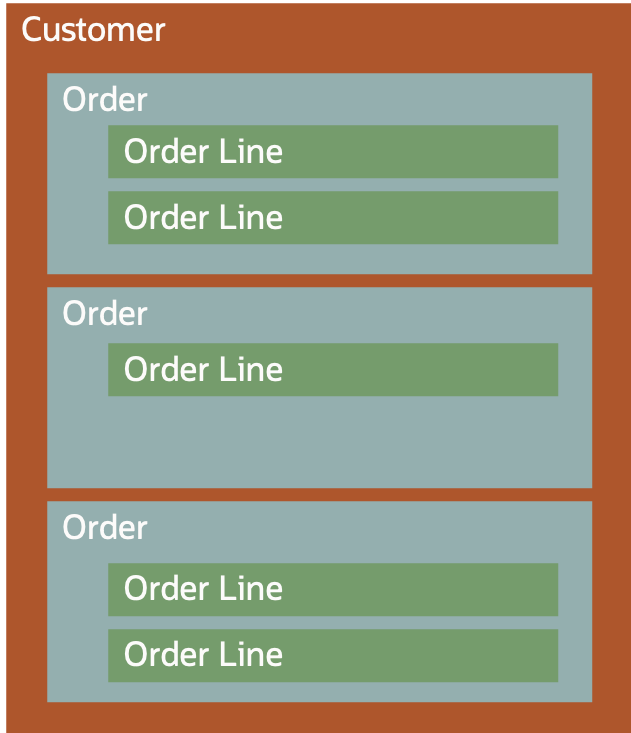

Let’s explain via an example, a customer places 3 orders over a year, each order comprising a few order line items. In this entity-object world, all this data is held together in a single multi-level data structure. The structure needs to be flexible because orders are added over time, and it’s possible for there to be one or many line items per order. Individual fields may or may not exist for a particular customer, order or line item.

This can be realised in code in a number of ways. A web app may hold everything as an xml or JSON document, a java app may hold it as a nested set of objects or (if you are old enough to remember) even COBOL might use an occurs-depending structure. JavaScript, Python and Perl would hold these as in memory structures of varying types. But what is common to all is that the data is accessed as a single structure for one instance of the customer. Another customer would have an entirely different instance of the object.

Relational

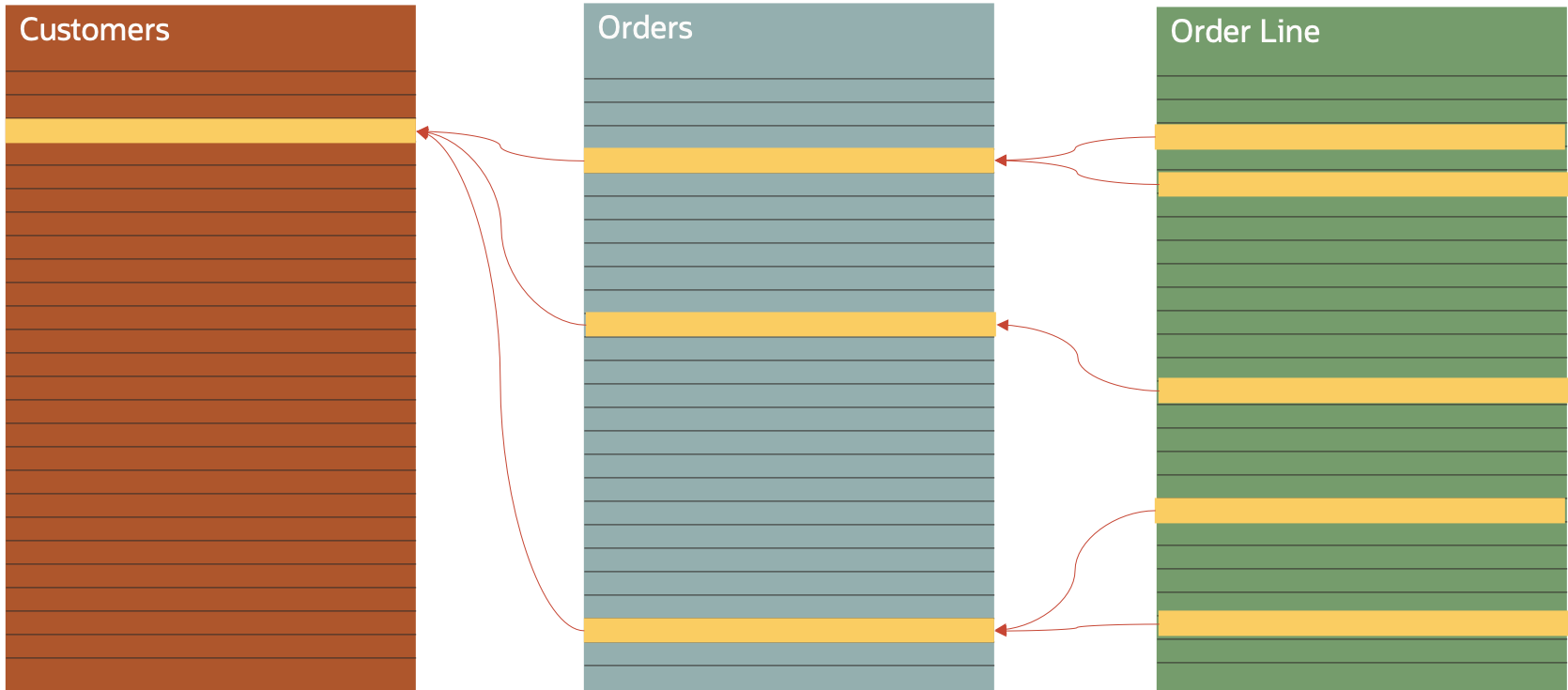

This model is fundamentally different. The data is separated into a 2 dimensional table for each entity. In its simplest form, this could be a spreadsheet with a worksheet (tab) for each entity, one for customer data, one for order data and one for order line data. Every row in every worksheet is given a unique identifier, and those identifier line across the worksheets. E.g. every order row will have a field holding the unique customer ID of the customer that placed the order. This structure is called a “normalised” structure.

The relational model is one based on and backed up by a rigorous mathematical model – relational algebra. It is closely related to set theory and shares many of the same operators that you may have met in high school (union, intersection, join etc).

It’s worth noting that the relational model is a mathematical construct to represent the relationships between data entities, and while a RDBMS might implement the relational model, the model exists in the data, regardless of the storage model

Why don’t we just choose one and throw away the other ?

Unfortunately, the reality is that, at least today, we need both viewpoints of the data that our organisations accumulate and generate. Let’s find out why by looking at application and analytics separately.

App development – object-entity rules !

For modern web applications residing on distributed networks by far the easiest and most effective model is the entity-object structure. The mobile app can make one request of the server for the customer, which then sends a single response of the single entire customer-order-orderline structure. These days the response will likely be a JSON string which the mobile app parses and maps directly into an in-memory object in one step. This object can be referenced quickly and easily via the built in object access methods.

If the server can only respond with relational data then three requests are required, one for each of the entities. As the data structure gets more complicated, then the number of requests increases.

Even when the mobile app has the three data sets, then it has to link and convert the datasets into a single entity-object model for efficient access with the app. This is also required for easy mapping to the browser document object model via one of the JavaScript dev frameworks.

The app can then manipulate the memory structures and when complete can send back the amended compete customer “document” to the server in one (e.g. as a REST PUT transaction).

Updating a relational structure is much more tricky. It requires a series of app-to-server interactions, one for every change to every “row”. Maybe insert an order, then separate inserts for each line item.

There are other issues with the relational model in this context. Every entity interaction needs to be bound to a specific entity description i.e. there would be one for the customer, one for the order, one for the line item. Even worse, these descriptions must match between app and server, and any time one changes, code on both sides would need to change. This is because the relational drivers (e.g. jdbc) are primarily driven by attribute order, and not attribute name. Although attribute name can be obtained from the query, this is laborious and non-intuitive. All our standards for relational data exchange are relatively poor in this regard, and mean that it’s easy for data mismatch to happen, and the interfaces are brittle.

Analytics

Analytics (and in this broad definition I include machine learning) has an entirely different set of needs. Whilst the web app deals with a single customer, analytics may deal with millions, tens of millions or even more. A simple count of the number of orders for a single product on a single day may mean traversing billions of order lines and selecting comparatively few. If every order line is embedded deep inside a complex and flexible customer structure, then the cost of parsing and traversing that structure is huge compared to the actual selection of the order line. Even worse, until we have opened and looked inside the structure, we can’t tell whether there is a order line we need, so the vast majority of the work we do is entirely wasted.

However, when the data is held in a two dimensional table, where the attributes are held in a fixed sequence, then scanning data becomes a trivial compute task. No parsing is required, just a simple read through the data structure using the ordinal position of the attributes to identify attributes and the end of rows. This structure also makes it easier to build secondary indexes of foreign keys e.g. a product id on a line item – and if this is possible, then in many cases counts of rows can be obtained from the index, and so there is no need to read the data structure at all.

There is a further optimisation of the relational model that is gaining wider adoption, and that is column oriented storage. This is where the data is stored by column rather than row. When held in this format, the user sees no difference and the SQL remains the same, but scans of the data are much faster. This is further accelerated by specialist support at the chip level with SIMD processing where many rows can be scanned in a single CPU clock cycle. Compare this to the many thousands of clock cycles required to parse even a single customer doc structure. This enables relational data structures to be scanned at far higher rates than document models, even when both are held entirely in memory. Scan speeds of over a billion rows per second are routinely witnesses on modest hardware.

Conclusion

There are good reasons why developers and DBAs and data analytics folks hold different viewpoints on the same data, and there is a clear need for those viewpoints to be available on the same data at the same time, whilst maintaining data integrity.

In a subsequent article I will look at the various options for modern applications that can enable those dual viewpoints.