Four Model

In a previous article I looked at why object-relational impedance was still a thing, and why we need both ways of holding data – object model to facilitate the easy interactions needed for user-facing applications, and relational for reporting and analytics on the same data.

So, the question that arises is how best can we optimise apps and storage so that both worlds of apps and data can get optimal value. Over time, various approaches have been used, and it might be useful to look a little at the history and see how the various ways of dealing with this challenge have been addressed.

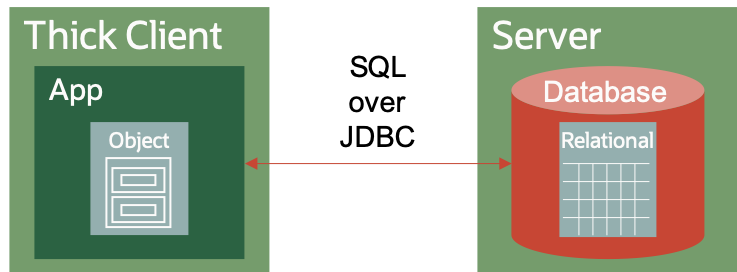

1. Client Server

In the early days of client-server (e.g. Visual Basic thick clients) and later java-based thick applications, the desktop applications would connect directly to the database using database specific protocols. The language required for the exchange was always SQL, and the protocol was odbc or jdbc.

This worked reasonably well, but suffered from a number of limitations:

- The limitations of the SQL knowledge of the developers often led to only a tiny subset of SQL being used (usually access by primary key only) and the result was inefficient database queries and large amount of data traversing the network

- The application became tightly bound to the database structure, so even a relatively simple change to the database (such as adding a column) could break the app

- The thick client applications often held open multiple database connections causing a large resource requirement on the server

In the world of client server, the developer mingled the object and relational models in the code, and every app seemed to find it’s own solution.

Although these were all challenges, it was a different challenge that really killed the client-server model – the need for updating the app on the desktop. The overhead of maintaining working versions of the VB or Java apps with the different versions of Windows, combined with poor desktop version management, resulted in organisations moving to deliver applications running in browsers – where the browser delivered the consistent desktop platform.

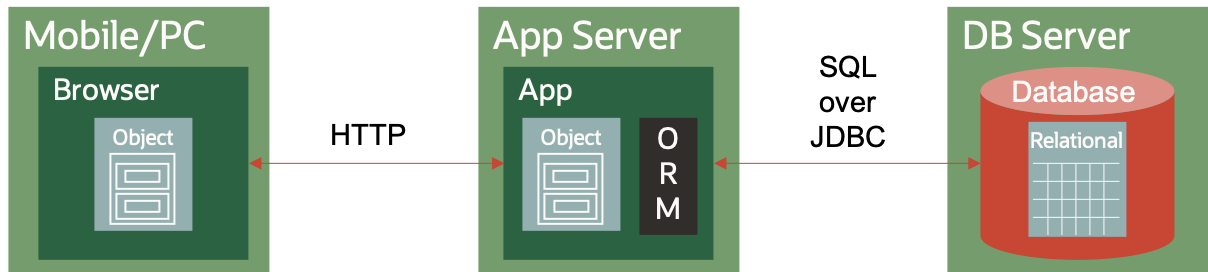

2. Web Application

As apps moved to browsers, the browser could only really communicate over HTTP – initially very basic form submission – and later XHTTPRequest. A great deal of the complexity was pushed down to a new middle tier – most frequently Java for enterprise apps.

The middleware (sometimes known as SOA) applications would accept the HTTP requests, and translate those into SQL to access the database, eventually sending HTML (or later JSON) back the the browser. It was in this period that Object-Relational Mapping tools became popular.

These were partially successful, and especially in that they meant that the app developer did not need to write SQL. Much of the complexity of using persistence was hidden from developers.

But these tools often failed to deliver on their promises. The core challenges were :

- The mapping was still part of the application developers domain, and so its configuration often suffered from a lack of database understanding

- The mapping frameworks themselves were often slow and cumbersome – leading to poor response times for end-users

- The mapping of complex objects was especially tricky and often led to a very high number of database interactions for a single end-user screen – again resulting in poor response times

- Often, to get a sufficiently fast response, the developer would end up coding “around” the ORM tool and resorting to SQL

In general the ORM model was seen to be “heavy” and cumbersome and it gradually fell out of favour.

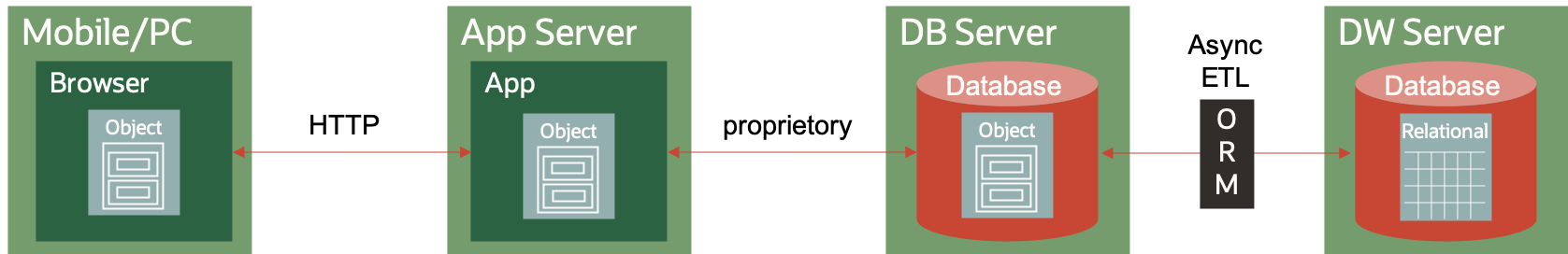

3. Document Store and Asynchronous ORM

By this time, developers were starting to look for simpler alternatives, and this drove the increasing interest in NoSQL alternatives – mostly key-value stores and document database. This hugely simplified the job of the developer. With the ability to store the entity-object directly on the server database, and retrieve pretty much directly into a memory structure, then developers could innovate and code much faster.

However, this left the challenge of reporting and analytics. Both document stores and key-value stores are primarily designed for row-at-a-time access, and they are very inefficient for the type of large-scale set-based processing typical of analytics and reporting.

This led to a compromise where a second database was needed to run the analytics. Often this was relational for business user reporting, and sometimes a third database was also added for more ad-hoc analytics – e.g. a Hadoop or similar platform, with ETL processes or streaming moving the data asynchronously.

This model suffered from some very significant challenges :

- Data was now in at least two, and possibly three databases with different fundamental structures, keeping them in-line because almost impossible

- downstream feeds from the application database would oven have a significant time lag, and data between the application and reporting would always see a lag

- The ETL processes required to extract, transform and load were costly to develop, difficult to maintain and very brittle to the high rate of change seen in the application

- The ETL and DW developers were very distant from the app developers (always in different teams) and so they rarely had the knowledge to be able to interpret the data correctly

While this model delivered excellent application developer innovation, it resulting in a decrease in the ability of the organisation to be able to report and analyse the data in the applications.

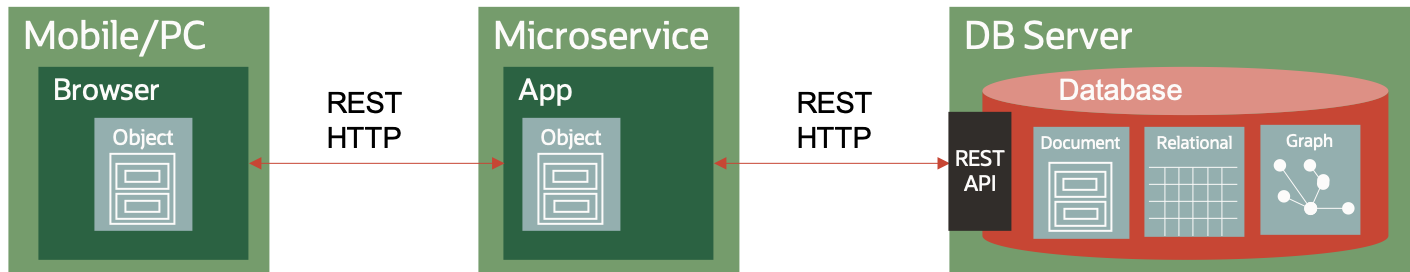

4. Microservices and Data Platform

The newest model that we see today, and perhaps the best solution so far is to allow the application domain (i.e. all the development teams) to be able to work in their native entity-object world, and to extend the responsibility of the database teams to now only provide the database functionality, but also a standard interface into the database that talks the object-relational language.

This is done by front-ending the database with an API that can present a native application interface – e.g. a document API, a key-value API, or even a graph API. Behind the API, the data platform persists the data in an appropriate structure. This may be document, object, relational, graph or other – whichever is best for that particular data entity. The data platform also provides a single converged query capability to allow access to all of that data regardless of the storage model.

Conclusion

We need to move past the object/relational battle and recognise that both are required in today’s complex data-driven environment. The combination of stateless microservices combined with a flexible multi-model data platform provides a firm foundation for today’s applications to deliver both application logic and analytical insight.