Some history

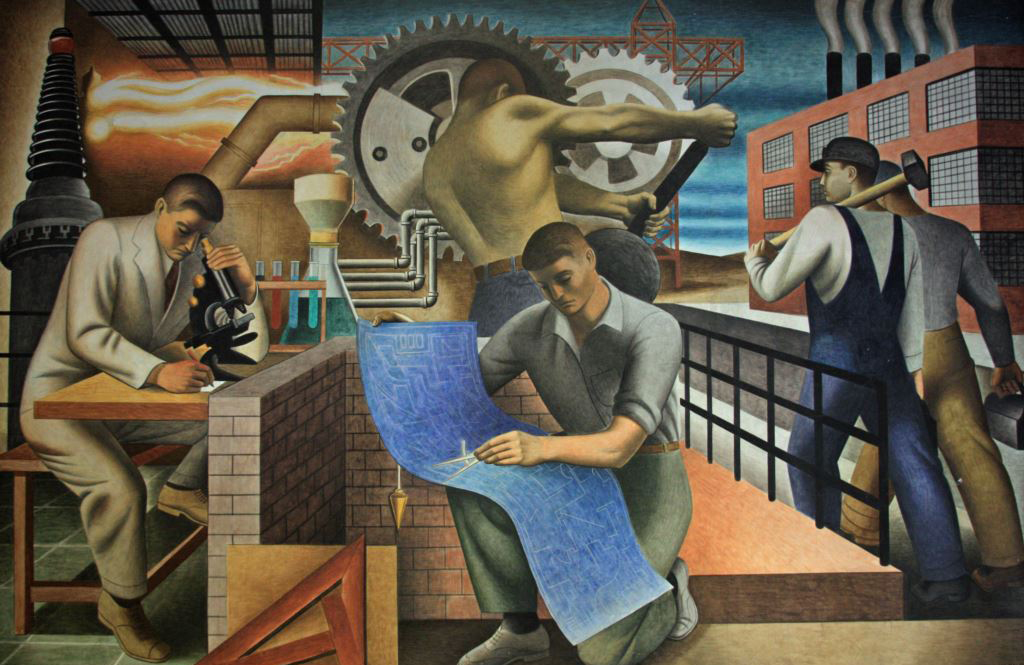

It is no exaggeration to say that the relative prosperity of the world today is fundamentally based on the division of labour. The division of labour enabled us to move from an agrarian society to build towns and cities, and then powered the industrial revolution. Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations put the division of labour and specialisation as one of the foundations of the industrial revolution. Today’s modern society means that every one of you reading this will have already specialised and will not be subsisting on what you can grow in your own garden.

Nearly everything we buy will have been mass produced by large companies using division and labour and extreme specialisation by the workers. Our buildings are constructed by an army of specialists – from bricklayers to quantity surveyors. Increasingly, automation is taking on many of those specialist tasks, and while that provides society challenges for income equality, there is no doubt that overall productivity increases as a result.

In science, again, we see specialism to an incredible day. While the body of science accessible to us all every day, the times when a polymath could know everything there was to know have long gone. Today, it’s virtually impossible to even know a tiny area I full detail.

Of course, there are exceptions. Some luxury cars may be made by small teams of people, and there is certainly a lot of people lovingly working at craft, taking basic materials and producing beautiful craftwork. But the result is almost always lower productivity and a higher price. <<link to Morgan video>>

Division of Labour in IT

Today’s IT organisations are the same. We have sys admin, DBAs, specialists for security, infrastructure, hardware and storage; project planners, testers, service managers, capacity planners, and so many flavours of developers that it’s hard to keep up. The IT world today is huge, and the need for specialism is everywhere with remuneration for true experts remaining very high.

Yet, today, we see a movement in the opposite direction. Microservices and Devops are pushing towards multi-discipline teams that cover every aspect of not only developing a solution, but running and maintaining that solution too.

So, this raises a number of questions

- what value does this approach offer

- why has this become necessary

- does the approach deliver long-term value

- is the approach generally applicable or only for some challenges

Let’s have a go at answering these one by one.

what value does this approach offer

First a quick summary of what I mean by the “approach”. I’m referring to a combination of ideas and architecture that are commonly linked together; microservices breaks down an application into discrete components, each component is built by a squad who is responsible for the both building and maintaining the function. They will typically use agile development approaches and utilise a CI/CD pipeline.

The focus of all of these concepts and approaches is speed of development of new functionality. Innovation levels can be very high, and with teams being almost self-sufficient, then decisions can be made quickly and new functions of products Brough to market extremely quickly.

The move of development processes from waterfall to agile has been going on for perhaps 25 years, but it is only now that architecture is truly enabling the innovation by breaking down the monolith. Agile techniques could only have minimal value when building a monolith, but when building a application built on Microservices, then the potential value of agile and devops can be realised.

So there is clear value – at least in terms of innovation and speed fo development. However, I should add that when I searched for “TCO” (total cost of ownership) applied to a microservices approach I found nothing quantitate – just a few statements that “it’s lower cost” with no evidence to back that up.

So I think we can say that the overall approach offers substantial value in terms of speed and innovation, but the jury is still out on long-term costs

why has this become necessary

Now we know the core benefit of the approach (speed) we can immediately see why this is necessary.

Over many years, the focus of IT departments worldwide has been on reducing the cost of IT while simultaneously improving the service levels of existing systems. It is quite common, possibly the norm, that CIOs are being asked to deliver more, with an ever reducing budget.

CIOs had no option but to lock down services to make them more resilient, and to squash innovation to reduce Capex – when every penny is being counted, trying out new ideas where 90% might fail is just not on the cards.

The result is that CIOs have pushed their IT organisations to use strong architecture governance, strict portfolio management and even stricter budgetary control to squeeze out all necessary expenditure. The result is a risk-averse culture and processes that seem to be there to stop things getting done (which, in many cases, is exactly what they are there for – to stop spend).

But then, along came the digital revolution. As consumers started to use digital services for more and more of their real-life activities, organisations who failed to deliver their services in a modern way quickly found themselves being driven out of the market by the newcomers.

Changing an entire IT organisation’s governance, culture and process to deliver digital services overnight is impossible. So, the outcome was this new modern approach – which was almost exclusively focused on innovation and fast delivery of a digital service. When an organisation is losing money to new competitors, suddenly IT budgets are no longer a barrier – faced with becoming obsolete, a little extra IT spend is easy to justify.

So, here was a marriage made in heaven – a new approach focused on innovation and speed, and an urgent need for fast deployment of digital services.

does the approach deliver long-term value

This is a harder question to answer – especially as applications and systems built in this way have only been around for a few years, and they are also primarily used in only a small subset of IT – predominantly for digital services as described above.

In general, there is a recognition that for some specific challenges that while the TCO is not clear, that using a more traditional approach (monolithic, waterfall etc) just could never have delivered a solution at all. So when there is no other option, then this approach is clearly the best.

Is the approach generally applicable or only for some challenges?

This area where this overall approach has had most success is in media delivery at global scale to hundreds of device types. Netflix, Spotify and Facebook have led the charge here and have delivered great results. However, much of the advice from those companies about this new approach is that it is very hard, and very costly, and that it should only be used when it is necessitated by a specific challenge, not used as the default approach for all types of development.

Where the main challenge of the application is business complexity – e.g. where the system is either highly process-driven or data-driven then then I think we need to proceed with a little caution. Both of those require a great deal of up-front design work which negates much of the benefit. Some examples of these might be a HCM system where we need to manage long complex regulated business processes; or a telco CRM system which supports multi-disciplinary service agents, or even an SCM system tightly coupled to financial processes; all of these would provide a significant challenge to an innovation led approach.

Conclusion

It’s clear that these is a class of IT problem where a micro-services/devops approach is best, and sometimes even the only approach. Equally, there are other business challenges where the need for a single, cohesive view across a complex area would be better served by a design-led approach.